In September of last year, Amnesty International released a report claiming Sudan air forces conducted at least 30 chemical attacks in the restive Jebel Marra region of Darfur. As many as 250 people were killed, and countless others injured. Two separate independent chemical weapons experts concluded the reported injuries and symptoms suggest a chemical attack from blister agents.

But these claims cannot be confirmed, or even properly investigated. Authorities continue to deny access, including for journalists, to the conflict regions within Sudan.

Sudan’s UN Ambassador Omer Dahab claimed the report was “baseless and fabricated.” Amnesty’s Sudan Researcher Ahmed Elzobier, however, is convinced traces of chemical agents would be revealed, if the independent media and others independent actors were granted access to Jebel Marra.

Instead, the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) appointed Sudan to their executive council’s vice-chairmanship in March, seemingly ignoring the report’s findings completely.

One of the world’s worst

The press freedom watchdog Reporters Without Borders ranks Sudan 174 out of 180 countries worldwide for good reason. Sudan remains one of the toughest places in the world to work for both local and international journalists and that is by design. The National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) ensure no journalist access to the conflict zones to control the narrative. “It is not easy for local and foreign reporters to access conflict areas in Sudan unless they have permission from NISS,” said journalist and press freedom advocate Abdelgadir Mohammed. “Moreover, local reporters are banned by law from reporting about the conflict zones, it counts as an alleged threat to national security.”

Journalists Daoud Hari and Phil Cox tried to investigate Amnesty’s chemical weapons claims in December but were tortured for the attempt. Cox recounts a harrowing story where Sudanese authorities detained them for nearly two months and interrogated them using techniques such as electrocution, asphyxiation and mock execution. Sudan’s press attaché to the Embassy in London, Khalid Al Mubarak, dismissed Cox in a Channel Four interview as a “desperate freelancer” who was paid to tarnish improving relations between the West and Sudan. Mubarak criticized Cox for not applying for a visa and entering the country illegally with smugglers.

“Obtaining any information from these regions in Darfur is an endless struggle”

–Award-winning photojournalist Adriane Ohanesian

But acquiring official access to Sudan’s conflict zones is challenging for foreign journalists.

“The government of Sudan makes it nearly impossible for journalists to report from Darfur,” said award-winning photojournalist Adriane Ohanesian, one of the few foreign journalists to enter Jebel Marra, after visiting the area in 2015. “Obtaining any information from these regions in Darfur is an endless struggle.”

Sudanese authorities rarely provide official access to Darfur, Cox told Nuba Reports, and monitor your movements closely. This makes it impossible to talk or film with local people openly without putting them in jeopardy. In the past, some foreign journalists gained access by traveling with rebel groups and without government visas.

“Now the government controls much of the terrain,” Cox said. “Today there is no independent access to Darfur without government control.”

A journalist from Darfur

IDPs in Sorotoni Camp, Darfur (Nuba Reports)

Reporting conditions for local Sudanese journalists – especially those from Darfur – are worse. Ahmed Suleiman*, a journalist from Darfur, says authorities increased their pressure on Darfur journalists after the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued a warrant to President Omar Al-Bashir in 2009, on charges of war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity. Since then, authorities assume any Darfur journalist or civil society member contributed to the research used in the ICC’s case against their president. A few years back, the national security forces detained Suleiman.

“The first question I was asked was about my tribe and hometown,” Suleiman said. “When the officer knew that I am from Darfur, he started beating me and verbally abusing me.”

Sudanese journalists covering Darfur have been tortured and threatened into silence, Suleiman told Nuba Reports, to the point where many stories are left untold.

“Cameras in the region are considered a crime”

–Darfur Journalist

“Cameras in the region are considered a crime,” he said. “Anyone who takes out a camera or takes pictures with a mobile phone is arrested, especially near the IDP (internally displaced persons) camps.”

Cases of rape or other violence against the displaced are never reported. Human rights violations by tribal militias and the notorious pro-government paramilitary Rapid Support Force are kept quiet – and journalists “always keep silent about what happens in Jebel Marra,” he said.

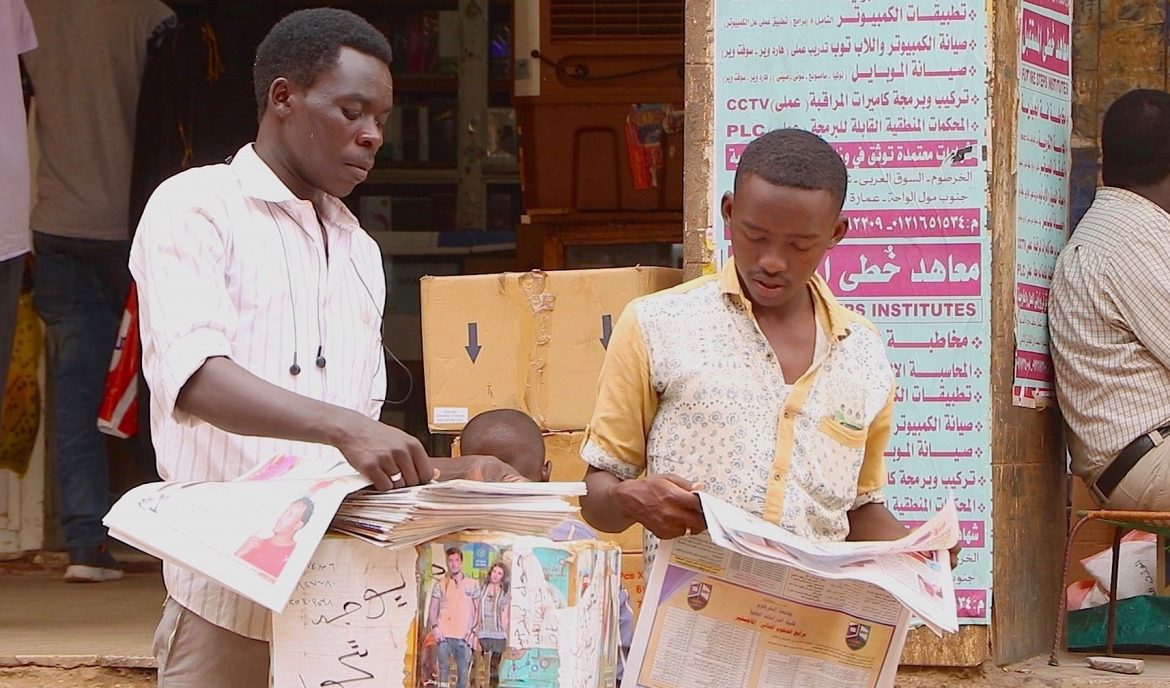

John Musa interviewing civilians in the Nuba Mts. (Nuba Reports)

The forgotten war

A similar media blackout pervades Sudan’s other conflict in what are known as the Two Areas: the Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile State. Despite over 4,000 bombs dropped on civilian targets since 2012 in the Nuba Mountains, the few international media outlets covering the conflict correctly refer to it as a ‘forgotten war’.

The remote location with limited access, coupled with the government’s efforts to block journalists reporting from the Nuba Mountains, has severely limited coverage, according to Musa John, a local journalist working with the only radio station, Kauda FM, in the rebel-controlled capital. Foreign journalists must sneak in to acquire access, John said, while local journalists “fear for their life, if they try to report here [the government] automatically accuses them of supporting the rebels.” As such, Khartoum ensures neither Sudanese citizens nor the international community have a clear picture about the Nuba Mountains, he adds. “You can imagine, when there is heavy fighting foreign journalists will come –perhaps once a year—but this does not give a full picture of events on the ground, especially for other issues besides the conflict,” John said.

Choosing to work as a journalist in the rebel-controlled areas of the Nuba Mountains is not easy. “There are so many challenges,” John said, “Lack of access, resources and the challenges of war –to name a few.” John, commonly referred to as ‘Mosquito’ by his peers since he is “always buzzing around” was hit by shrapnel from a warplane bombing a village near Al-Azrak on World Press Freedom Day last year. “I felt like I went to my grave and was brought back again.”

This media blackout occurs at a time when Sudan enjoys unprecedented engagement with western governments. The US government may permanently drop 20-year economic sanctions in July with the caveat that Khartoum upholds a cessation of hostilities in the conflict zones until then. The European Union is handing Khartoum millions of Euros to curb African migrant flows into Europe. Without independent monitoring on the ground, however, there is little indication Sudan needs to uphold its part of the bargain.

“I personally believe in engagement with Sudan,” Cox said, “But there needs to be much more transparency, clear conditions of success and failure and foresight when discussing trade, immigration, security and development –especially when using UK and EU taxpayer money.”

Sudan’s security vs. the press

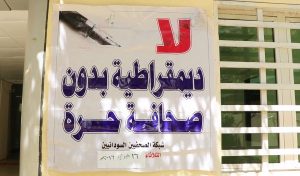

“No Democracy without a Free Press” –a sign reads outside offices of Al-Tayyar Newspaper (Nuba Reports)

While Sudan’s constitution ostensibly upholds press freedom, Sudan’s security forces wield unhindered authority over the media where press conditions could go from bad to worse. Between late November and December last year, NISS confiscated 32 print runs – that compares to a total of 33 in the first nine months of the year, according to the press freedom organization Freedom House. Security-led print confiscations hit the independent Al-Jareeda 27 times, Chief Editor Ashraf Abdel-Aziz said, costing the media house over $30,000 in lost revenue. “Now NISS controls everything from newspaper advertisements, to movement permits for journalists, to reporting –even the editorial line,” Mohammed told Nuba Reports.

“Now NISS controls everything from newspaper advertisements, to movement permits for journalists, to reporting –even the editorial line”

–Journalist and Author Abdelgadir Mohammed

NISS maintains its broad powers through the sweeping 2010 National Security Act, said Elzobier, Amnesty’s Sudan researcher. “The legislation provides the agency unlimited discretion to decide what constitutes a political, economic or social threat and how to respond to such threats.”

The National Dialogue – a presidential initiative launched in 2014 ostensibly to end the armed conflicts and improve political freedoms – concluded with the resolve to curb the security force’s powers. But amendments to Sudan’s constitution presented to parliament in February have largely been ignored without any substantial changes to the status of Sudan’s security service, Elzobier said.

With NISS powers unchecked, chances of greater media access to the conflict zones appear unlikely. Despite this vacuum, western governments are increasingly engaging with Sudan’s security forces in separate bids to counter terrorism and curb migration –with little means to monitor and evaluate this engagement. While the state censorship may shift focus from time to time, Mohammed believes press freedom conditions in Sudan are continually declining. “The international community must pressure Khartoum to allow press freedom first before engaging with them,” Mohammed said. This, he believes, is the only way to reverse this trend of Sudan’s ever shrinking press freedom.

* Name changed to protect identity