SUDAN INSIDER |

This news summary is part of our Sudan Insider, a monthly newsletter

providing news and analysis on Sudan’s biggest stories.

Subscribe here to receive the Sudan Insider in your inbox.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

US sanctions against Sudan lifted after 20 years

What happened…

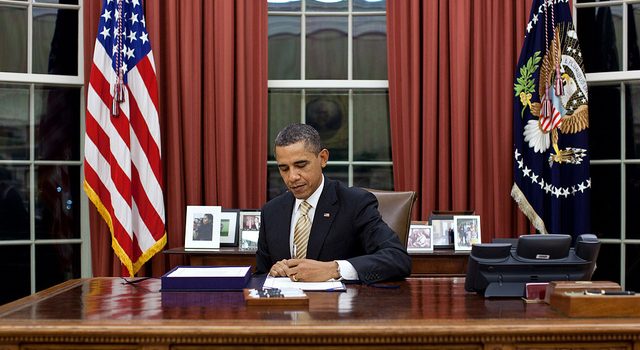

U.S. President Barack Obama, in one of his final actions in office, issued an executive order on January 13 provisionally lifting most sanctions on Sudan. This move was a reversal from his October signature to renew the sanctions. Former President Bill Clinton first imposed sanctions on Sudan in 1997 for its role in supporting international terrorism and efforts to destabilize neighboring governments and human rights violations.

Individual sanctions placed on seven government, militia and rebel leaders in connection with the conflict in Darfur issued in 2006 will remain in place, as will bans on trade in weapons.

The move was reportedly based on progress in: a decrease in military operations in the three conflict areas, improved humanitarian access, refrain from assistance to rebels in South Sudan and counter-terrorism intelligence support to the West. The January executive order provided for the issuance of a general license, allowing open trade over a provisionary six-month period. By July 12, 2017, the secretary of state is to provide a report to the president that will provide the basis for reviewing the sanctions suspension.

Obama’s foreign policy of engagement, as witnessed in other countries such as Cuba and Iran, argues that open trade – linked with the threat of renewing sanctions – will offer more leverage than blanket sanctions alone.

President Trump will have the option of re-enacting sanctions, issuing another temporary reprieve, or permanently removing the sanctions. Obama administration officials have reportedly consulted the Trump administration on the policy shift.

What it means…

The U.S. move has sparked intense debate. Many who oppose the removal of sanctions argue that the situation has not changed and that the administration is taking too much on faith. President Omar al Bashir, for instance, has pledged and breached at least six ceasefire agreements since the conflict in the Nuba Mountains began six years ago. The same government reneged on two signed internationally brokered humanitarian access agreements, in February 2012 and August 2013.

With little trust in the ruling National Congress Party (NCP), critics believe Sudan will not fulfill its pledge to desist military operations and allow humanitarian access to war-affected areas. And in the absence of independent media and civil society reporting, the U.S. government may find itself hard-pressed to challenge the government’s account of the situation on the ground.

Critics question the official reasons given for lifting the sanctions. The State Department cited reforms to Khartoum’s humanitarian directives under the government Humanitarian Aid Commission (HAC) and access to Golo in the restive Jebal Marra, Central Darfur region. Given HAC’s reputation for blocking international aid into Darfur, critics suggest little weight can be given to written amendments to their humanitarian access procedures. Further, access to Golo only comes after Sudan achieved a military victory in the area where Amnesty International alleges the potential use of chemical weapons.

The sanctions lift comes at a time where there is no peace process, much less an agreement, and still no agreement over humanitarian access in the two war-affected areas of South Kordofan and Blue Nile states. The State Department appears to be rewarding Sudan over select criterion for the sanctions lift, including its alleged counter-terrorism intelligence and non-interference in South Sudan, over other humanitarian considerations beyond a cessation in hostilities and marginal improvements to access in some areas. The former U.S. Special Envoy to Sudan and South Sudan, Donald Booth, has said counter-terrorism efforts alone would not have been enough to yield this shift in U.S. policy.

The question of how to even assess progress is problematic, as Khartoum continues to crack down on independent voices. In November and December of 2016 alone, 32 newspaper print runs were confiscated in Khartoum with devastating financial impact for affected papers (by way of comparison, 33 were confiscated throughout the first nine months of the year). In addition, arrests under the IT Crime Act increased in 2016, seeing journalists arrested for messages posted on social media. Meanwhile, human rights monitors and reporters continue to be banned from the conflict areas.

With rocketing inflation rates reaching 29 percent and currency account deficits reaching nearly $4 billion, coupled with disparate budget expenditure for security purposes, the ruling NCP was facing an economic crisis and potentially subsequent political collapse before the U.S. sanctions were lifted. Critics claim the State Department’s decision has provided a notorious regime a chance to retain a fragile hold on power by avoiding further protests from a growing opposition. The debate is still ongoing over whether mass civil disobedience protests against fuel subsidy cuts last year had any political influence. The wide-ranging level of participants in the protests, however, that includes many young Sudanese with no former political background, cannot be disputed.

The six-month probationary period for the lifted sanctions has, however, undoubtedly improved conditions for civilians living in the war affected regions of the Two Areas of South Kordofan and Blue Nile states. President Bashir announced a six-month ceasefire for all conflicts within Sudan directly after the U.S. decision to lift sanctions. While this ceasefire has already been breached in Blue Nile and Darfur, no bomb attacks against civilians have been reported. This may mean a well-deserved respite for citizens during crucial planting seasons in the two conflict areas.

Supporters of the U.S. policy shift point out that the 20-year old sanctions were ineffective: the conflicts in Darfur and Two Areas – replete with gross human rights abuses – continued unabated despite American sanctions. This is partly due to the fact America has failed to lift sanctions in the past for requirements that Sudan has fulfilled such as agreeing to the separation of South Sudan in 2011. The United States had lost political leverage vis-à-vis Sudan in this regard.

Supporters also pointed out that generalized sanctions had unintended consequences. Instead of harming the leadership, they argue, sanctions harm ordinary people by denying citizens access to goods. While the State Department set up exemptions to curb this, many financial institutions insisted on a blanket ban on trade with Sudan, fearing heavy fines for breaching the sanctions. In May 2015, a judge ordered the French bank BNP Paribas to pay $8.83 billion for violating U.S. sanction on Sudan over an eight-year period.

The sanctions provided the NCP a useful scapegoat to redirect criticism over poor governmental economic policies largely designed to help the regime maintain power with little consideration for growth. By lifting the sanctions, Sudan authorities may no longer be able to downplay the impact of the regime’s costly wars and corruption.