Roughly 70,000 refugees have resettled in South Sudan’s Yida camp just over the Sudan border, and they may soon be forced to start their lives over once again.

They have come to Yida to escape ongoing war in the Nuba Mountains between Sudan’s armed forces and a rebel group since it began in 2011. Fighting continues; Nuba Reports documented 2,000 bombs dropped in civilian areas last year alone. Come June next year, the settlement where the Nuba people have started markets, developed farms, built schools and even an airstrip, will be effectively shut and refugees relocated to other camps, says the UN.

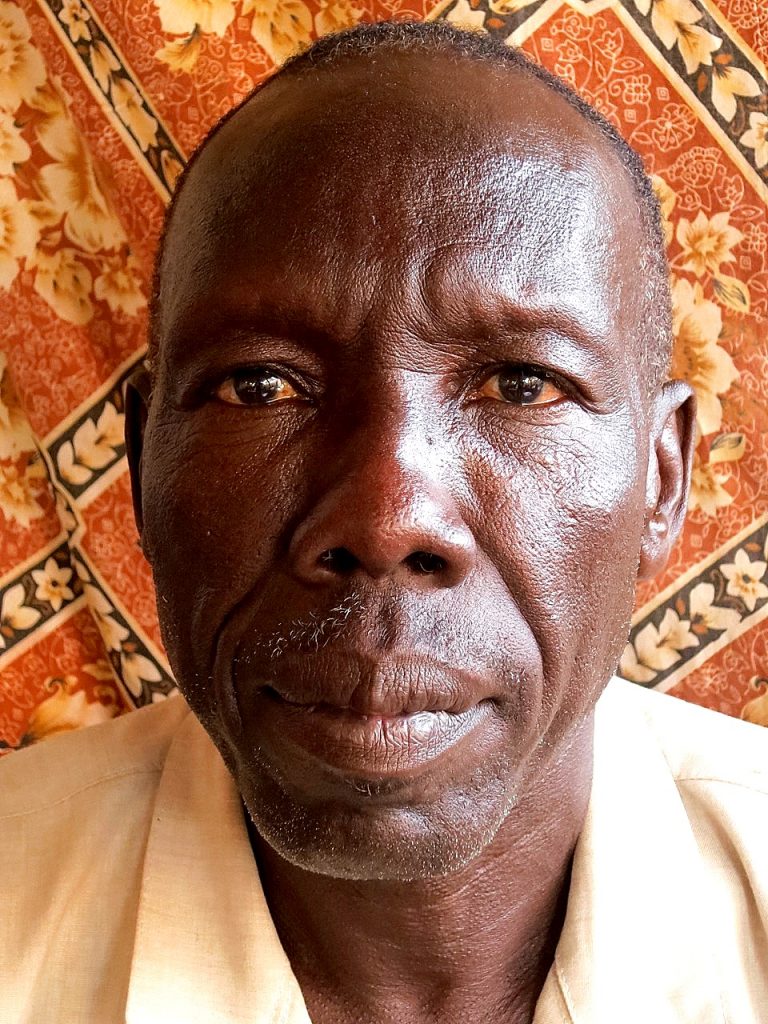

The refugees have struggled to build their lives anew since fleeing war. “We came from Nuba with nothing and our homes were destroyed. We were forced to come to a different country to survive,” explains Ali Kuku Mekki, Paramount Chief at Yida. Before NGOs and the UN started serving the refugee population there, Nuba refugees had set up Yida camp–replete with a bustling market, now the largest in Unity State, as well as volunteer-run schools. “We have farms and businesses that help us provide what we need, then the UN tells us close your things and stop your work–you must move again,“ Mekki told Nuba Reports.

During a recent consultative meeting between the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, and Yida residents, UNHCR delegate Nigora Kadirhojaeva told Yida residents the camp would be closed in mid June, according to Al Nour Salih, Chairman of the Yida Refugee Council who attended the meeting. Only select vulnerable groups such as the elderly and disabled would receive limited, non-food supplies such as mosquito nets and plastic sheeting, he added.

Instead, the UN agency and South Sudan’s Refugee Affairs Commission are pushing Yida residents to Ajuong Thok and another proposed camp called Pamir, yet to be started, where food rations and other services are provided, UNHCR South Sudan Representative Juliette Stevenson told Nuba Reports. Currently registration of new arrivals to Yida continues, Stevenson added, but since 2013 food rations are only provided to newcomers if they relocate to Ajuong Thok camp.

UNHCR and the Government of South Sudan say Yida has never been an officially recognized refugee camp and never can be, despite the 70,166 refugees registered there. This is for two main reasons, says Rocco Nuri, Public Information/Communications Officer at UNHCR: the camp’s proximity to the Sudan-South Sudan border, and “armed elements” in the camp.

Yida is 14 kilometers from the Sudan-South Sudan border, less than the 50-kilometers minimum set by UN guidelines. But Ajuong Thok is just 2 kms further away than Yida and Pamir, based on a UNHCR map, is a similar distance from the border.

The negligible difference in kilometers between the camps not only fails to meet the UN guidelines, but the location of the alternative camps is less secure, according to Yida residents. “The UN told us that Yida is too close to the border and for that reason it is insecure. That is why we must move,” Mekki said. “But for us from Nuba we see Yida as much more secure than other places.” Ajuong Thok is only 45 km from a Sudanese government army base, according to the Deputy Chairman of the Yida Refugee Council, Ismail Hussein, the very people Yida refugees fled from in the first place. The upcoming Pamir camp is also located in an area with several nomadic tribes who are in conflict with Yida residents, Hussein added. “You find people and tribes who kicked us out of our homeland in the Nuba Mountains,” Hussein said, “It is also [in an area] controlled by South Sudanese rebel forces so it is not safe and not in the hands of the government of South Sudan. These two reasons made us scared to go to Pamir.” In comparison, the Yida camp provides an escape route that Nuba refugees think safe to make their way home should they want to, several Yida residents told Nuba Reports.

UNHCR, however, claim there are armed elements operating in Yida camp making it unsafe for refugees or humanitarians to operate there. According to Stevenson, Yida is too close to a border that is in dispute between Sudan and South Sudan and its militarization by armed groups compromises its suitability as a refugee site. Refugee Chairman Salih, however, disputes this claim. Salih concedes that armed groups from Darfur, western Sudan, were present in Yida camp in the past but claims the South Sudan army forced the armed groups to leave the camp and “followed after the armed group to make sure they left.”

A dispute over the resources available for refugees in Yida as opposed to Ajuong Thok also persists. “Having seen Yida and Ajuong Thok, I’d live in Ajuong Thok because of the services, “ Nuri said. “Education is free, better health care replete with a primary healthcare clinic and people in need of referral are transferred to Pariang County Hospital which we are supporting.” Based on UNHCR data, water accessibility is better in Yida but malnutrition and child mortality rates remain lower in Ajuong Thok in comparison to Yida. But Salih and other Yida residents claimed those living in Ajuong Thok lack adequate food and face poor health services and that UNHCR statistics do not accurately portray the camp’s conditions since many residents there are not registered. In fact, several Yida residents told Nuba Reports that Ajuong Thok residents are returning to Yida due to limited food rations at Ajuong Thok where refugees cannot farm outside the camp to make ends meet.

The key difference for the Nuba refugees between the two camps concerns self reliance: the host community allows Yida residents to farm and set up markets while those in Ajuong Thok do not, Salih told Nuba Reports. “Yida is different,” he said, “the host community here gives refugees a chance to farm and get charcoal, in Ajuong Thok our people are not allowed outside [the camp], even if to get grass or something.”

Farming is increasingly important for the refugees to have enough to eat as the World Food Programme (WFP) struggles with funding and cuts food rations, WFP Senior Regional Spokeswoman Chaliss McDonough told Nuba Reports. Funding shortfalls have forced WFP to reduce the size of rations for refugees in South Sudan by 30 percent since August, she added.

Yida refugee Fadila Kafi Jamus, a 35-year old mother of 6 from Logori, Nuba Mountains, said she relies on farming to feed her family and to sell extra produce for salt, soap and clothes for her children. “The food from the UN is not enough for my family,” she said, “but with the food that I farmed it will be enough for my children and I.”

Concerns of overpopulation in Yida is another reason cited by UNHCR. In a 2013 interview with UNHCR’s former head of operations in Unity State, Marie-Helene Verney, voiced their concerns of having potentially 100,000 refugees in one place. “We know what that means from other countries, we know the problems of health, with availability of water, with security the problems that come with that [overpopulation] and we fear the same for Yida too.”

But Yida residents are understandably wary of relocation due to past experience. In 2012, UNHCR asked Yida’s 30,000 residents to move to another refugee camp, Nyeli. The local refugee council insisted that the land in Nyeli was prone to flooding, and would soon be a swamp, virtually unlivable, according to several Yida residents. But UN officials pushed ahead, and the small fraction that moved were again homeless just one year later when flooding made Nyeli inhabitable and the UN was forced to close the camp.

As it stands, many in Yida remain in a state of limbo –unsure whether they can continue harvesting and building or whether they must pack up once more for another settlement. “We as Nuba flourished in this place, each has their own work, some are farming and traders started their business,” said Al-Kheir Mojid, a Yida refugee and trader. “And now when the UN asked us to move, it will make us struggle again.”